What Can We Learn From Traditional Indian Rainwater Harvesting Systems?

By: Muskan Aggarwal | Date: 12th August 2018

It is not an obscure fact that water is one of the most primary resources for survival and with its replenishable nature, it is still the resource on the brink of exhaustion with the population still not coming to terms with it. But all is not lost, there have been attempts at restoration and that in itself is a step towards awareness and conscientiousness, and rainwater harvesting systems take the centre stage in it.

You must be aware that the Indus valley civilization had been famous for its irrigation and water harvesting techniques and thus when it comes to RWH, India has its pride. But why is it that despite having such an elaborate system and knowledge, the country is facing such extreme water shortage conditions.

We will come to that aspect later, but foremost we should get ourselves acquainted with the concept of rainwater harvesting and the various techniques employed, both tradition and modern so as to gain an understanding of both.

Rainwater harvesting is the accumulation and storage of rainwater for reuse on-site, rather than allowing it to run off. Rainwater can be collected from rivers or roofs, and in many places, the water collected is redirected to a deep pit (well, shaft, or borehole), a reservoir with percolation, or collected from dew or fog with nets or other tools. Its uses include water for gardens, livestock, irrigation, domestic use with proper treatment, indoor heating for houses, etc.

The harvested water can also be used as drinking water, longer-term storage, and for other purposes such as groundwater recharge. Rainwater harvesting is one of the simplest and oldest methods of self-supply of water for households usually financed by the user.

The gruelling summer seasons, the quick exhaustion of groundwater, and contamination of water resources have added to the decrease in our resources and thus it becomes imperative that we make the most of our rainy seasons and harvest as much water as we can.

In India around 83% of available fresh water is used for agriculture. Rainfall being the primary source of fresh water, the concept behind conserving water is to harvest it when it falls and wherever it falls.

The importance of storing rainwater through different techniques can be understood by an example of the desert city of Jaisalmer in Rajasthan which is water self-sufficient despite experiencing meager rainfall as against Cherrapunji, which is blessed with the highest rainfall in the world, but still faces water shortage due to lack of water conservation methods.

Now we come onto the traditional methods of RWH:

Drawing upon centuries of experience, Indians continued to build structures to catch, hold and store monsoon rainwater for the dry seasons to come. These traditional techniques, though less popular today, are still in use and efficient.

Here is a brief account of the unique water conservation systems prevalent in India and the communities who have practised them for decades before the debate on climate change even existed.

1. JHALARAS

Jhalaras are typically rectangular-shaped stepwells that have tiered steps on three or four sides. These stepwells collect the subterranean seepage of an upstream reservoir or a lake. Jhalaras were built to ensure easy and regular supply of water for religious rites, royal ceremonies and community use.

The city of Jodhpur has eight jhalaras, the oldest being the Mahamandir Jhalara that dates back to 1660 AD. The typical lifespan of Jhalaras is around 20-30 years. Built with large investment of money and numerous skilled laborers, these magnificent structures today stand discarded by society.

2. BAWARIS

Bawaris are unique stepwells that were once a part of the ancient networks of water storage in the cities of Rajasthan. The little rain that the region received would be diverted to man-made tanks through canals built on the hilly outskirts of cities.

The water would then percolate into the ground, raising the water table and recharging a deep and intricate network of aquifers. To minimise water loss through evaporation, a series of layered steps were built around the reservoirs to narrow and deepen the wells.

3. TAANKAS

Taanka is a traditional rainwater harvesting technique indigenous to the Thar desert region of Rajasthan. A Taanka is a cylindrical paved underground pit into which rainwater from rooftops, courtyards or artificially prepared catchments flows.

Once completely filled, the water stored in a taanka can last throughout the dry season and is sufficient for a family of 5-6 members. An important element of water security in these arid regions, taankas can save families from the everyday drudgery of fetching water from distant sources.

4. JOHADS

Johads are small earthen check dams which store rain water. They constitute high elevation in three sides, a storage pit,and excavated soil for fourth side.

Some johads are interconnected through deep channels, with a single outlet in a river or stream to prevent structural damage. This cost-efficient and simple structure requires annual maintenance of de-silting and cleaning the storage area of weed growth.

5. PANAM KENI

It is a specia type of well to store water used by the Kuruma tribe, made by soaking the stems of toddy palms so that only the hard-outer part remains which is them made into a wooden cylinder.

These cylinders are then immersed in groundwater springs in fields and forests.this explains why they have abundant water even in hottest months.

6. KUND

A saucer shape catchment area with a slope towards the centre. Usually harvests water for drinking. Traditionally, these well-pits were covered in disinfectant lime and ash, though many modern kunds have been constructed simply with cement.

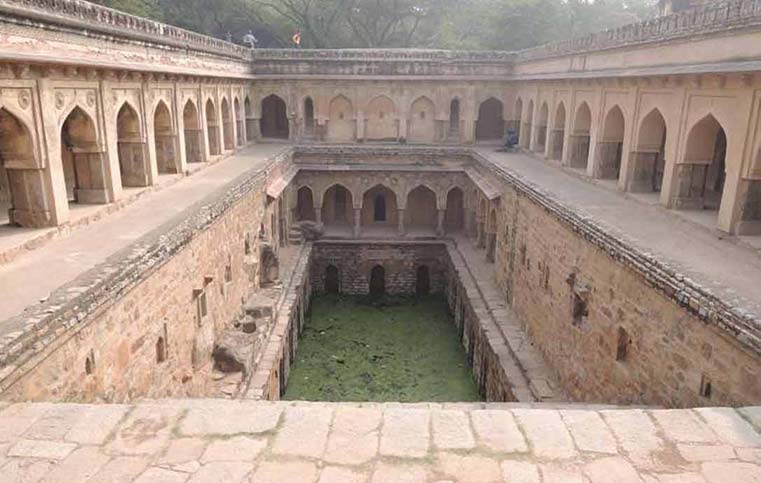

7. BAOLI

Secular structure for everyone to draw water from. Made with beautiful arches, carved motifs and stepwells, they also had rooms on their sides. The location of a baoli revealed its usage. Baolis within villages were mainly used for utilitarian purposes and social gatherings.

Baolis on trade routes were often frequented as resting places. Stepwells used exclusively for agriculture had drainage systems that channelled water into the fields.

8. NADI

Strategic village ponds that store rainwater collected from adjoining catchment areas. Since nadis received their water supply from erratic, torrential rainfall, large amounts of sandy sediments were regularly deposited in them, resulting in quick siltation.

9. ZABO

Also known as the Ruza system. Its channels collect rainwater that falls on forested hilltops which is then deposited in pond like structures on the terraced hill sides. The channels also pass through cattle yards, collecting the dung and urine of animals, before ultimately meandering into paddy fields at the foot of the hill. Ponds created in the paddy field are then used to rear fish and foster the growth of medicinal plants.

10. JACKWELLS

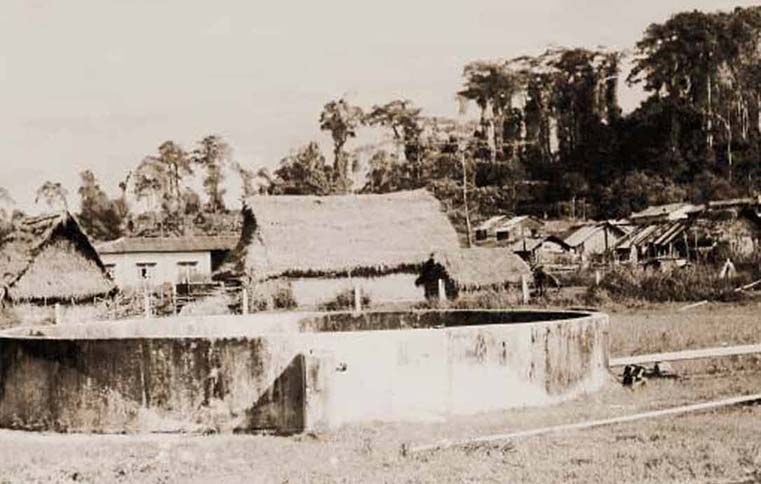

The Shompen tribe of the Great Nicobar Islands lives in a region of rugged topography that they make full use of to harvest water. In this system, the low-lying region of the island is covered with jackwells (pits encircled by bunds made from logs of hard wood). A full-length bamboo is cut longitudinally and placed on a gentle slope with the lower end leading the water into the jackwell.

Often, these split bamboos are placed under trees to collect the runoff water from leaves. Big jackwells are interconnected with more bamboos so that the overflow from one jackwell leads to the other, ultimately leading to the biggest jackwell.

11. KHADIN

Khadin is a water conservation system designed to store surface runoff water for the purpose of agriculture. It entails an embankment built around a slope, which collects rainwater in an agricultural field.

This helps moisten the soil and helps in preventing the loss of top soil. Additionally, spillways are provided to ensure that excess water is drained off. This system is common in the areas of Jaisalmer and Barmer in rajasthan. A dugwell is made a bit further from khadin to take advantage of recharging groundwater around the structure.

12. VIR DAS

They are shallow wells dug withina natural depression. Since the area around is very saline, when rain water seeps down the soil, it collects over the saline groundwater due to the difference in density (rainwater being less dense).

The tribesmen identify areas on basis of flow of the monsoon runoff and build these shallow wells. This smart method helps them separate freshwater from saltwater and provide water for a variety of purposes.

13. RAMTEK MODEL

The Ramtek model has been named after the water harvesting structures in the town of Ramtek in Maharashtra. An intricate network of groundwater and surface water bodies, this system was constructed and maintained mostly by the malguzars (landowners) of the region.

In this system, tanks connected by underground and surface canals form a chain that extends from the foothills to the plains. Once tanks located in the hills are filled to capacity, the water flows down to fill successive tanks, generally ending in a small waterhole. This system conserves about 60 to 70 % of the total runoff in the region!

14. ERI

The Eri (tank) system of Tamil Nadu is one of the oldest water management systems in India. Still widely used in the state, eris act as flood-control systems, prevent soil erosion and wastage of runoff during periods of heavy rainfall, and also recharge the groundwater.

Eris can either be a system eri, which is fed by channels that divert river water, or a non-system eri, that is fed solely by rain. The tanks are interconnected in order to enable access to the farthest village and to balance the water level in case of excess supply. The eri system enables the complete use of river water for irrigation and without them, paddy cultivation would have been impossible in Tamil Nadu.