Floodwater Storage to Address Water Woes

– Deciphering The “Good Floods, Bad Floods” Notion

By: Nishikant Gupta | Date: 12th September 2019

Image Source: TOI

Image Source: TOI

The district of Pune in the Indian State of Maharashtra lies in the rain shadow zone of the Western Ghats and is dominated by a semi-arid climate.

Despite the historical dependence of some residents on the existing watersheds here, pollution, encroachment, low conservation awareness, and the scarcity of targeted policies result in water shortages. Lately, disasters such as floods are slowly gaining a foothold here.

Various climate models project an increase in mean temperature by 2050 across the region compared to a 1960s baseline.

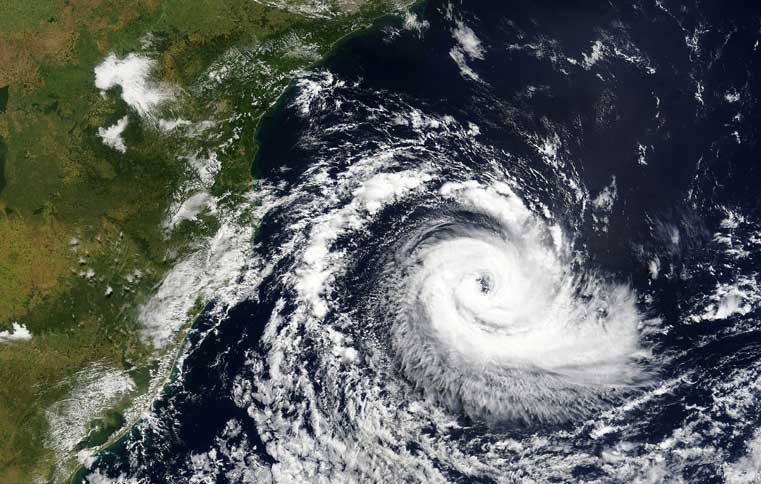

The monsoon is expected to become longer and less predictable; precipitation is projected to vary on average; and the intensity of extreme rainfall events is likely to increase. These have the potential to affect river discharge and possibly lead to more flooding events.

Floods can cause economic and livelihood losses, in addition to the tragic loss of lives. Low-income earners are at the forefront of the adverse impacts of floods. Their asset base can be diminished due to the destruction of standing crops, dwellings, infrastructures, and machinery, often resulting in significant financial burdens. Nonetheless, some argue that floods can also bring benefits.

Image Source: California WaterBlog

Image Source: California WaterBlog

For example, floods can recharge the dwindling groundwater reservoirs; make the agricultural soil more fertile by increasing nutrients in some soil types; provide water resources in drier regions; play a possible role in maintaining ecosystems in river corridors; and can spread nutrients to lakes and rivers, possibly leading to increased biomass and improved fisheries for dependent local communities.

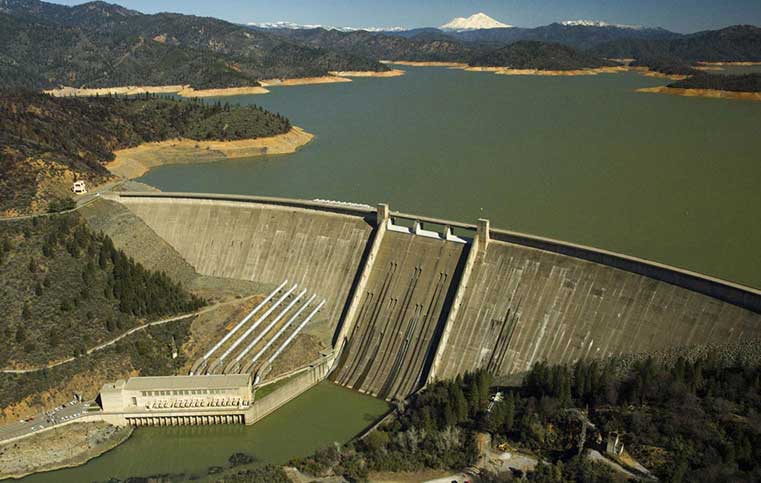

Within this ongoing debate between the adverse and positive impacts of floods, floodwater storage is one possible strategy which could be explored to understand its applicability both within the urban and rural landscape.

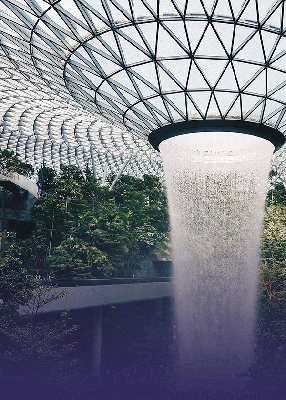

To begin with, artificially created ponds/water bodies in identified flood-affected areas can help in storing the excess water during a flood event. Here, the revival of traditional water reservoirs could also greatly assist in this approach.

This stored water can then be used for irrigation during drier periods (by building canals, small water reservoirs, and sluice gates), potentially enhancing agricultural production and livelihood security of local communities.

In addition, purification of this stored water and resupply within the existing municipal system can also provide some respite during the drier months when water availability is at its lowest.

Summing up, critical pressures such as floods urgently require the application of targeted management strategies, and envisaging their economical uses to enhance the wellbeing of local communities could be a way forward.