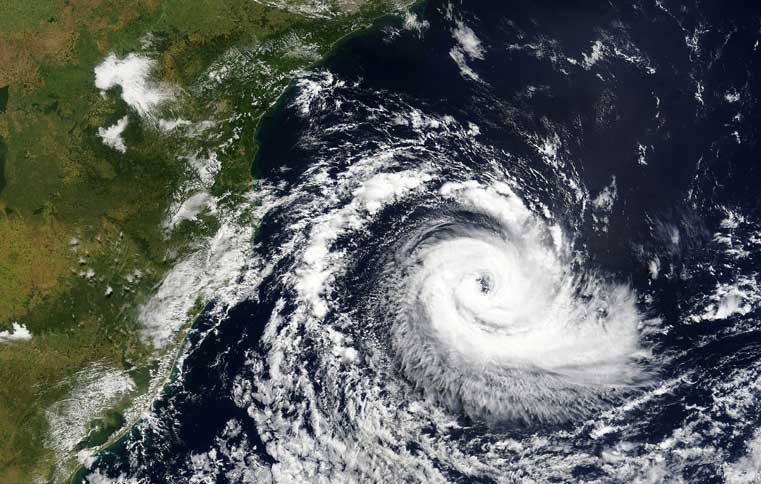

Urban Floods: Could The Application of Traditional Knowledge Work Towards Building Resilient Cities?

International Day for Disaster Risk Reduction 2019

By: Nishikant Gupta | Date: 18th October 2019

Image Source: Deccan Herald

Image Source: Deccan Herald

“Get up Nishikant, the water is coming in rapidly. We are going to drown.” It is not the nicest of feelings when you are awakened in the middle of the night by vigorous shaking.

My mother was visibly upset, tears filling up to the brim of her eyes, as she pointed towards the bedroom door. I quickly grabbed my spectacles from the bedside table to get a clearer view, and almost leapt further inside the bed.

A steady flow of water was gushing into our bedroom from the space underneath the door. My father was hurriedly lifting anything he could get his hands on from the lower elevations of the room and placing them on top of anything higher than him.

“Need you awake, son,” my father’s tone was stern.

I quickly rushed towards the bathroom and grabbed a bucket. I started filling it using the glass next to the bed.

My mother looked at me for a couple of seconds and then screamed, “Grab a mug or something larger will you please.”

As I ran back to the same spot with a water jug this time, the water was ankle deep. “That came in fast,” I thought to myself.

I quickly filled up the bucket and ran towards the front door of our room. As I frantically opened the door, I froze.

“Throw the water out and come back to collect more,” it was my father again. I did not respond.

I was stunned. Before me was the front porch of our house – completely submerged.

“Where do I throw it?” I asked myself.

The water level was now slowly moving up from my ankles towards my calves.

The flooding in our house, (a temple for my parents, as it probably is for everyone else), left a lasting adverse impact, both financially and psychologically, on us. I have long argued with my two sisters that it was a ‘chance’ event, one which neither my parents nor I had ever envisioned.

Nonetheless, as we observed the water level rise up to our knees by the early morning, I watched my mother’s eyes swollen red as she stared at our ancestral bed float around the room like a sailboat.

As the early morning light crept in from behind the curtains, I remember wading through the muddy water to reach the main road, only 100 metres away from our gate. The sight was extremely depressing.

On my left, I saw a mother in a sari, carrying her daughter high on her shoulders while she remained waist deep in water. She was all the while looking around anxiously holding a long stick.

I soon figured out why. A long, slender, dark shape swam away from her in the distance.

On the right, I witnessed a gory sight. A heavily pregnant buffalo was shaking vigorously against an electric pole. The owner along with a few other men, was desperately trying to push her away using bamboo sticks.

I was quickly pulled back by a passerby. “Beta (son), don’t go there. There is electric current in the water”. When I turned back, the buffalo was motionless.

Looking straight ahead, I could hear a horse cart owner mercilessly whipping his animal and urging it to keep going. The horse struggled to make ground in the turbid water, which enveloped him up to his thighs.

Having to heave 10 men made matters worse for him. The passengers refused to get down in the “dirty water”, and the animal was losing its strength. I quickly waded in the oil and grease laden water, and tried to push the cart forward.

Within minutes, a few others joined as well. When we managed to help the animal move ahead, there was a loud neigh.

The Oxford English Reference Dictionary (2019) defines flood as “an overflowing or influx of water beyond its normal confines, especially over land”. An event with a definition so innocuous has often been the reason for the loss of numerous lives and livelihoods.

Whether it was the devastating 2013 floods of Uttarakhand in North India, or the disastrous Koshi flood in 2008 in Bihar, India, the loss of lives were in their thousands and the loss of livelihoods in billions. The future doesn’t look too bright for communities living along these dynamic rivers.

Changes in extreme precipitation events have been observed in the numerous river basins of the Hindu Kush Himalayan region in the last few decades. Flooding patterns are projected to change due to the impact of climate change on the hydrological regime, and the intensity of rainfall events is expected to increase in the river basins here.

The flooding event of that morning left a lasting impression on me. Along with that came a question which bothered me for days – “We lived in a good locality, had plenty of green spaces around, and a drainage system on the main road.

How did the water then enter our house with such a short spell of rain?”

I spoke to my father a week after the terrible tragedy had affected our town and our home. I began by asking how things were when he was a child, and how things had gotten so bad now.

As he sipped his morning tea watching my mother tend to her home garden, he took a deep breath and began. “Ancestral knowledge of dealing with floods has long been forgotten.

When your grandfather built this house, he made sure there was plenty of mud and grass around to allow the water to percolate below.

He planted trees which could hold the mud together, and give beautiful flowers and fruits. In our locality, before a new construction came up, we often discussed with our neighbors – we made sure the excess water had a way out”.

He took another sip of his steaming tea. “Look around you now. Forget your neighbors, look at the surroundings of our own house. The ground is cemented for the sake of making it beautiful! Our trees are now the “pretty ones” which neither give fragrant flowers nor juicy fruits. What about the plants which could have helped during this flood?

No one cares about them now. Look at our drainage systems. They are clogged with rubbish which we throw, and are only cleaned before the arrival of the monsoons. What if the monsoons came early – they did this time and you saw what happened?”

My mother interjected as she placed the freshly-picked lemons on the table. “Why are we not always prepared? Just the other day I read that we now have projections for everything, but they are not 100% reliable. How is that helpful then? Why not improve these projections with the knowledge of the people who have been there, seen it all, and suffered year after year?”

My parents had raised more questions than provided answers. But, they had a point. “So what now?” I asked.

“Well, speak to the elderly. You know, we might be old-fashioned, but we have plenty of knowledge and wisdom. You young generation do not have the time to tap into what is freely available.

This knowledge will disappear with our generation”. My father also had his unique way of making me feel guilty for settling away from home.

He began again. “Let’s have an overhaul in our thinking Nishikant. Nature is all around us, and ready to help us out, but only if we seek its assistance. Let’s bring in local knowledge before jumping into new construction projects.

Why not have the local knowledge system triangulate between one’s own understanding and official systems? It’s not always how beautiful your house looks you know, it’s also about how resilient it is”.

I quickly interrupted jokingly, “You remembered the word.”

He smiled as he got up to leave, “It’s time your generation does too.”